“A bold plan to grow seedlings on the Moon by 2026 has been funded by the Australian Government, in what could reveal a greater understanding of horticulture in extreme environments.

The Australian Lunar Experiment Promoting Horticulture (ALEPH) project led by local start-up Lunaria One – with RMIT, QUT and ANU as the major Australian university partners along with industry bodies – has just received $3.6 million as part of the Australian Space Agency’s Moon to Mars Initiative.

Investigating whether seedlings can grow on the lunar surface is of fundamental biological interest and important to know for possible future space exploration, but it could also teach us more about growing plants in a changing climate here on Earth.

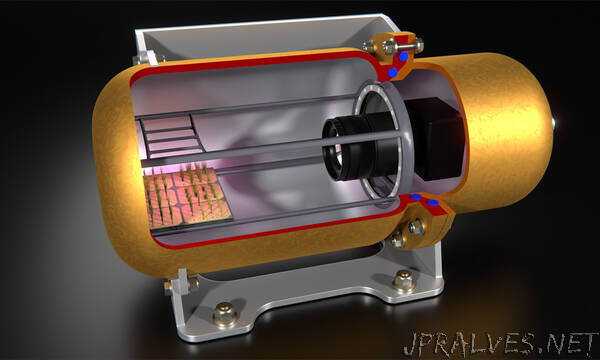

Lunaria One co-founder and engineering lead for the project, RMIT’s Dr Graham Dorrington, said the seeds and plants will be transported in a specially designed and hermetically sealed chamber – equipped with sensors, water and a camera – aboard a lunar lander scheduled for a mission in 2026.

“Our major challenge is designing the chamber to maintain suitable conditions to permit germination on the lunar surface, where the external surface temperature fluctuates from highs of 80°C to lows of –180 °C,” said Dorrington, from RMIT’s School of Engineering.

The chamber also needs to be lightweight – no more than 1.5 kg – and able to operate on minimal power while transmitting data via the lander back to Earth, using data rates of less than 40 kb/s.

“These are considerable challenges, but we have the necessary staff and facilities here at RMIT to succeed,” he said.

RMIT will also contribute expertise in plant biology from the School of Science, led by Associate Professor Tien Huynh.

“We know some plants grow differently in altered gravity conditions, but don’t yet fully understand how and why,” she said.

“In addition, the harsh lunar environment has a thin atmosphere, rapidly changing temperatures, and relatively poor soil properties, meaning that whatever we grow on the surface will need to be hardy.”

One of the plants being considered for the mission is Rapeseed (Brassica napus), a yellow-flowered plant grown for a range of food production and industrial uses.

“Preliminary results suggest this could be a good candidate as far as extreme temperature tolerance and germination speed for surviving a mission to the Moon or Mars,” Huynh said.

After landing on the lunar surface, the plants’ growth and general health will be monitored and data and images will be beamed back to Earth. RMIT will also be contributing computer science expertise for data compression to enable this part of the operation.

RMIT Deputy Vice-Chancellor STEM College and Vice-President, Professor Ian Burnett, said the cross disciplinary research could provide valuable insights into how to support horticulture in extreme climates on Earth.

“We view the development of this lunar payload as an excellent opportunity to tackle extreme engineering and biological challenges that will likely lead to terrestrial benefits as well as answers for space exploration,” he said.

Citizen scientists and school children from around the world will be invited to use this data to conduct their own experiments into which plant varieties have the best chance of growing on the Moon.

Lunaria One Director, Lauren Fell, said the central value guiding this project was that space exploration is for everyone.

“We don’t want a future where only autonomous and remote-controlled machines inhabit realms beyond earth, but where humans can live and thrive,” she said.

“The key to this is to get humans involved and to give them a say in how we get there. The ALEPH project aims to open up the science and engineering behind growing life on the Moon so that anyone can be involved.”

The collaboration with Lunaria One will bolster RMIT’s growing space industry eco-system, united under the university’s Space Industry Hub.

In all, a dozen RMIT engineers, scientists, educators and industrial design students are contributing to the project.

Ben Gurion University in Israel will contribute their expert knowledge to the plant biology team, coordinating the inputs of international experts. ANU will organise supporting workshops.”