“Strange diamonds from an ancient dwarf planet in our solar system may have formed shortly after the dwarf planet collided with a large asteroid about 4.5 billion years ago, according to scientists.

The research team says they have confirmed the existence of lonsdaleite, a rare hexagonal form of diamond, in ureilite meteorites from inside the dwarf planet.

Lonsdaleite is named after the famous British pioneering crystallographer Dame Kathleen Lonsdale, who was the first woman elected as a Fellow to the Royal Society.

The team – with scientists from Monash University, RMIT University, CSIRO, the Australian Synchrotron and Plymouth University – found evidence of how lonsdaleite formed in ureilite meteorites and published their findings in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) journal. The study was led by geologist Professor Andy Tomkins from Monash University.

One of the senior researchers involved, Professor Dougal McCulloch from RMIT, said the team predicted the hexagonal structure of lonsdaleite’s atoms made it potentially harder than regular diamonds, which had a cubic structure.

“This study proves categorically that lonsdaleite exists in nature,” said McCulloch, Director of the RMIT Microscopy and Microanalysis Facility.

“We have also discovered the largest lonsdaleite crystals known to date that are up to a micron in size – much, much thinner than a human hair.”

The team says the unusual structure of lonsdaleite could help inform new manufacturing techniques for ultra-hard materials in mining applications.

What’s the origin of these mysterious diamonds?

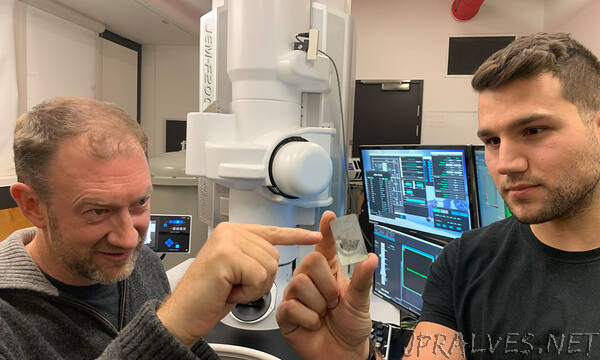

McCulloch and his RMIT team, PhD scholar Alan Salek and Dr Matthew Field, used advanced electron microscopy techniques to capture solid and intact slices from the meteorites to create snapshots of how lonsdaleite and regular diamonds formed.

“There’s strong evidence that there’s a newly discovered formation process for the lonsdaleite and regular diamond, which is like a supercritical chemical vapour deposition process that has taken place in these space rocks, probably in the dwarf planet shortly after a catastrophic collision,” McCulloch said.

“Chemical vapour deposition is one of the ways that people make diamonds in the lab, essentially by growing them in a specialised chamber.”

Tomkins said the team proposed that lonsdaleite in the meteorites formed from a supercritical fluid at high temperature and moderate pressures, almost perfectly preserving the shape and textures of the pre-existing graphite.

“Later, lonsdaleite was partially replaced by diamond as the environment cooled and the pressure decreased,” said Tomkins, an ARC Future Fellow at Monash University’s School of Earth, Atmosphere and Environment.

“Nature has thus provided us with a process to try and replicate in industry. We think that lonsdaleite could be used to make tiny, ultra-hard machine parts if we can develop an industrial process that promotes replacement of pre-shaped graphite parts by lonsdaleite.”

Tomkins said the study findings helped address a long-standing mystery regarding the formation of the carbon phases in ureilites.

The power of collaboration

CSIRO’s Dr Nick Wilson said the collaboration of technology and expertise from the various institutions involved allowed the team to confirm the lonsdaleite with confidence.

At CSIRO, an electron probe microanalyser was used to quickly map the relative distribution of graphite, diamond and lonsdaleite in the samples.

“Individually, each of these techniques give us a good idea of what this material is, but taken together – that’s really the gold standard,” he said.

‘Sequential Lonsdaleite to Diamond Formation in Ureilite Meteorites via In Situ Chemical Fluid/Vapor Deposition’ is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) (DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2208814119).”