“The limited system made a notable advancement on the road to beating classical machines.

In the race to create a quantum computer that can outperform a classical one, a method using particles of light (photons) has taken a promising step forward. Jian-Wei Pan and Chao-Yang Lu, both at the University of Science and Technology of China, and their colleagues improved a quantum computing technique called boson sampling to achieve a record 14 detected photons in its final results. Previous experiments were capped at only five detected photons. The increase in the number of the particles is small, but it amounts to a 6.5-billion-fold gain in “state space,” or the number of ways in which a computer system can be configured. The larger the state space, the less likely a classical computer can perform the same calculation.

The result was reported in a paper posted at the preprint server arXiv.org on October 22 and has yet to be peer-reviewed. But if it is confirmed, it would be an important milestone in the race for quantum-computational supremacy—a fuzzy goalpost defined as the point where quantum computers outpace their best classical counterparts.

THE BEAN MACHINE

In classical computers, information is encoded in binary bits, so two bits could be 00, 01, 10 or 11. A quantum computer can be in every classical state simultaneously: two qubits have some probability of being 00, 01, 10 and 11 until they are measured; three qubits have a probability of being in any of eight states; and so on. This exponential increase in information illustrates why quantum computers have such an advantage—in theory.

Over the past few weeks, the race for quantum computational supremacy has reached a breakneck pace. Google’s quantum computer performed an operation that its scientists claim would take a classical computer 10,000 years in just 200 seconds. IBM researchers, who are also working on a quantum computer, have expressed doubts, suggesting a classical computer could solve that problem in under three days.

Pan and Lu argue in their paper that their technique is another possible route toward quantum supremacy. “I’m not sure—it looks hard,” says Scott Aaronson, a theoretical computer scientist at the University of Texas at Austin, who was not involved with this research. “But, you know, as a co-inventor of boson sampling, I’m gratified to see to see progress along that route as well.”

Boson sampling can be thought of as a quantum version of a classical device called the bean machine. In that device, balls are dropped onto rows of pegs, which they bounce off of, landing in slots at the bottom. The random motion of the balls typically leads to a normal distribution in the slots: most balls fall near the center, and fewer fall toward the sides, tapering off at the edges. Classical computers can easily simulate random motion to predict this result.

Boson sampling replaces the balls with photons and the pegs with optical devices such as mirrors and prisms. Photons are fired through the array and land in a “slot” at the end, where detectors register their presence. Because of photons’ quantum properties, a device with just 50 or 60 photons could produce so many different distributions that classical computers would take billions and billions of years to forecast them.

But boson sampling can predict the results by carrying out the task itself. In this way, the technique is both the computational problem and the quantum computer that can solve it.

Aaronson and his then student Alex Arkhipov proposed boson sampling in 2010, but it has languished behind other quantum computing methods that use physical qubits, such as the techniques favored by Google and IBM. Part of the trouble is its limited utility. “A universal computer can solve any different type of problem,” says Jonathan Dowling, a theoretical physicist at Louisiana State University, who was not involved with the research. “This can only solve one.” But solving just one problem faster than a classical computer would count as a demonstration of quantum-computational supremacy.

A HORSE RACE

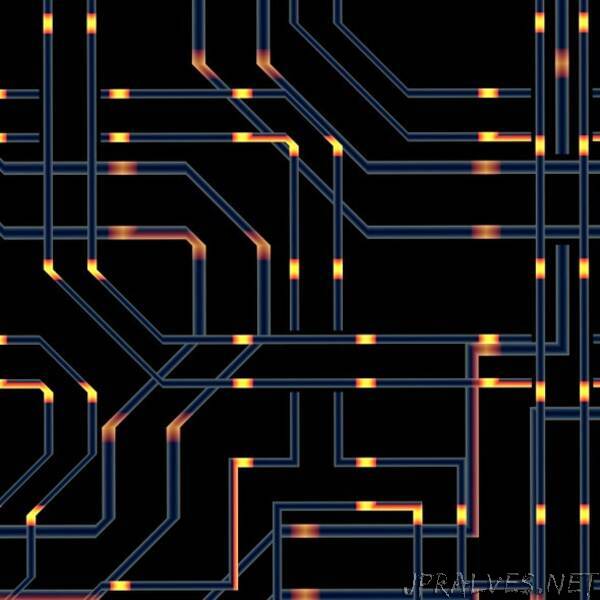

Performing the experiment, though, is easier said than done. On Twitter, Lu shared a picture of his team’s experimental setup, a tabletop covered in an intricate pattern of densely packed, gleaming metallic devices. The real difficulty is the timing: the team needed to produce single photons separately and simultaneously. “Photons aren’t going to wait for each other, so you need to generate every photon at the same time,” says Alexandra Moylett, a Ph.D. student in quantum computing at the University of Bristol in England, who was also not involved in the work.

If the photons arrive even a few trillionths of a second apart, they become “lost.” Each photon in the system increases the chance that there will be photons out of sync, because error will compound error. The more photons are lost, the easier it is for a classical computer to simulate the photon distribution, and the further you get from quantum-computational supremacy. Lu credits the team’s increase to 14 detected photons to an extremely precise photon source. “That’s the magic ingredient,” Dowling says. “Otherwise, they wouldn’t be able to do this.”

Although the researchers detected only 14 out of 20 input photons, that number was enough to generate a hard-to-compute state space. To understand why, consider the simple game of tic-tac-toe, where the state space is 19,683, or 39, because each of the nine squares has three possibilities: a blank space, an X or an O. The previous best boson-sampling study’s state space was 15,504, whereas the one for Pan and Lu’s experiment was roughly 100 trillion. In a Twitter post, Lu claimed that within a year, his team would increase the number of photons to between 30 and 50.

Whether or not boson sampling can scale up to reach quantum computational supremacy remains unclear. Many questionable claims have come before—some with multimillion-dollar businesses based around them. “Quantum supremacy is like a horse race where you don’t know how fast your horse is, you don’t know how fast anybody else’s horse is, and some of the horses are goats,” Dowling says. But this result, he clarifies, is not a goat.”