“We are one of several teams who recognized the challenges faced by Italian physicians, and are working to find a solution to the anticipated global lack of ventilators. In the US alone, the COVID-19 pandemic may cause ventilator shortages on the order of 300,000-700,000 units (CDC Pandemic Response Plans). These could present on a national scale within weeks, and are already being felt in certain areas. An increase in conventional ventilator production is very likely to fall short and with significant associated cost (paywall warning).

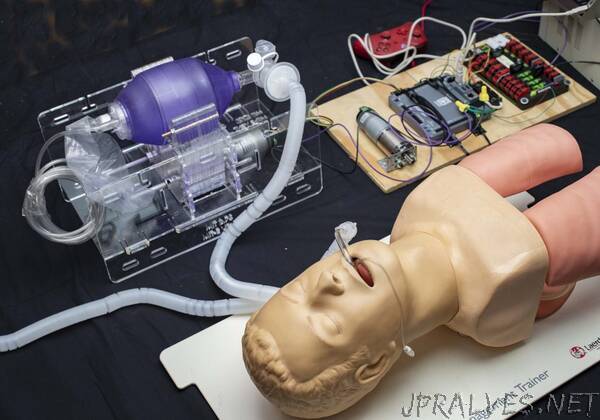

Almost every bed in a hospital has a manual resuscitator (Ambu-Bag) nearby, available in the event of a rapid response or code where healthcare workers maintain oxygenation by squeezing the bag. Automating this appears to be the simplest strategy that satisfies the need for low-cost mechanical ventilation, with the ability to be rapidly manufactured in large quantities. However, doing this safely is not trivial.

Use of a bag-valve mask (BVM) in emergency situations is not a new concept. A portable ventilator utilizing an ambu-bag was introduced in 2010 by a student team in the MIT class 2.75 Medical Device Design (original paper here and news story here), but did not move past the prototype stage. Around the same time, a team from Stanford developed a lower-cost ventilator for emergency stockpiles and the developing world. It looks similar to a modern ICU ventilator (Onebreath), but “production for US hospitals would start [in] about 11 months”, making it “a second wave solution” (MIT Tech Review Article). Last year, the AMBU® Bag concept was re-visited by two student teams, one from Rice university (here & here), and another Boston-based team who won MIT Sloan’s Healthcare prize (MIT News: Umbilizer). Other teams currently working on this challenge can be found linked on our “Additional Resources” page.

Key Research Question

We have launched an emergency research project with a team of MIT Engineers and American clinicians to address the question:

Is it possible to safely ventilate a COVID-19 patient by automatically actuating a manual resuscitator?

Our process in approaching this question is to first identify the minimum requirements for a low-cost ventilator, based on the collective wisdom of many clinicians, design against these requirements, conduct immediate testing, report the results, iterate and facilitate discussion.

Manual ventilation with an Ambu-bag is a short-term solution in a critical care environment, without any apparent clinical evidence regarding the safety of long-term use (days-weeks). There are multiple scenarios in which respiratory support could be needed: patients can be awake or asleep, sedated or sedated and paralyzed, breathing spontaneously, weaning off of a vent, etc. Furthermore, changing clinical presentations with ARDS require shifting minute ventilation (tidal volume x respiratory rate) to “lung-protective” strategies, which place patient’s at risk for things like auto-PEEP. Some of these situations are simpler than others, with the simplest being ventilating a sedated, paralyzed patient, and at a minimum a safe emergency ventilator could be used in such a situation to free-up a conventional ventilator.

Any solution should be utilized only in a healthcare setting with direct monitoring by a clinical professional. While it cannot replace an FDA-approved ICU ventilator, in terms of functionality, flexibility, and clinical efficacy, the MIT E-Vent is anticipated to have utility in helping free up existing supply or in life-or-death situations when there is no other option.

Further, any low-cost ventilator system must take great care regarding providing clinicians with the ability to closely control and monitor tidal volume, inspiratory pressure, bpm, and I/E ratio, and be able to provide additional support in the form of PEEP, PIP monitoring, filtration, and adaptation to individual patient parameters. We recognize, and would like to highlight for anyone seeking to manufacture a low-cost emergency ventilator, that failing to properly consider these factors can result in serious long-term injury or death.

Open Source Design

At the present time, we are producing four sets of material, which we will be releasing and updating on this site in an open-source fashion:

Minimum safe ventilator functionality based on clinical guidance

Reference hardware design for meeting minimum clinical requirements

Reference control strategies and electronics designs and supporting insights

Results from testing in animal models

We are releasing this material with the intent to provide those with the ability to make or manufacture ventilators, the tools needed to do so in a manner that seeks to ensure patient safety. Clinicians viewing this site can provide input and expertise and report on their efforts to help their patients.

As with any research to design to scale-up to manufacture, we anticipated that there will be many problems and it is our goal to provide this site as a tool to “close the loop” and receive feedback. We will also do our best to publish the most relevant pieces of information in the discussion forum for all to see.

We invite anyone who is interested to follow this work.”