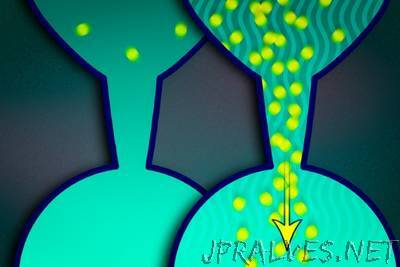

“When many people try to squeeze through a passageway at the same time, it creates a bottleneck that slows everyone down. It turns out the reverse is true for electrons, which can move through small openings more quickly when travelling in large groups than when flying solo.

The theory of so-called superballistic flow predicts that electrons can pass more easily through constrictions by interacting with one another, and thereby “cooperating,” than they can individually. The theory was proposed in a paper earlier this year by a team led by MIT professor of physics Leonid Levitov.

Now, in a paper published this week in the journal Nature Physics, a team at the University of Manchester in the U.K., working alongside Levitov and MIT undergraduate Haoyu Guo, have confirmed the theory in an experiment employing devices built from an atomically thin layer of graphene.

The idea behind superballistic flow is that interactions among electrons make them move in a highly coordinated manner, mimicking the behavior of particles in highly viscous fluids.

When electrons traveling individually pass through a constricted opening, they will bounce off the walls at either side, losing their momentum as well as some of their energy.

But when the electrons travel in dense groups, they are much more likely to bounce off each other than the walls. Such electron-electron collisions are known as “lossless,” since the total energy and the net momentum of the two particles are conserved. The momentum of individual electrons can change rapidly in the process, however the overall momentum conservation ensures that the losses are very low.

As a result, together the electrons are able to travel more quickly, and pass through the constriction more easily, than they would alone.

“Viscous flows of electrons have been anticipated in theory but never observed, partly because the materials were not good enough at the time, and partly because there were no good proposals of what to look for,” Levitov says.

To make viscous flow easier to identify, Levitov’s theoretical paper suggested forcing electrons to travel through a constriction, generating an electric current. This is a similar idea to the way in which 19th century researchers studied viscosity by passing fluids through a narrow channel.”