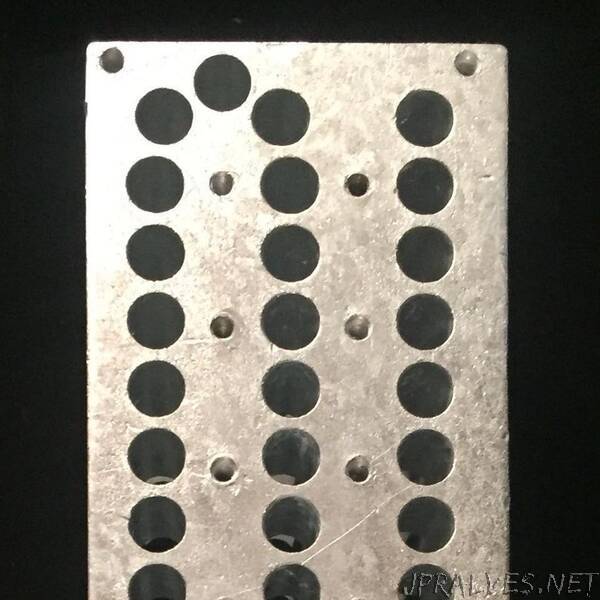

“A new “quantum flute” experiment by University of Chicago physicists could point the way towards new quantum technology. The holes create different wavelengths, akin to ‘notes’ on a flute, that can be used to encode quantum information.

University of Chicago physicists have invented a “quantum flute” that, like the Pied Piper, can coerce particles of light to move together in a way that’s never been seen before.

Described in two studies published in Physical Review Letters and Nature Physics, the breakthrough could point the way towards realizing quantum memories or new forms of error correction in quantum computers, and observing quantum phenomena that cannot be seen in nature.

Assoc. Prof. David Schuster’s lab works on quantum bits—the quantum equivalent of a computer bit—which tap the strange properties of particles at the atomic and sub-atomic level to do things that are otherwise impossible. In this experiment, they were working with particles of light, known as photons, in the microwave spectrum.

The system they devised consists of a long cavity made in a single block of metal, designed to trap photons at microwave frequencies. The cavity is made by drilling offset holes—like holes in a flute.

“Just like in the musical instrument,” Schuster said, “you can send one or several wavelengths of photons across the whole thing, and each wavelength creates a ‘note’ that can be used to encode quantum information.” The researchers can then control the interactions of the “notes” using a master quantum bit, a superconducting electrical circuit.

But their oddest discovery was the way the photons behaved together.

In nature, photons hardly ever interact—they simply pass through each other. With painstaking preparation, scientists can sometimes prompt two photons to react to each other’s presence.

“Here we do something even weirder,” Schuster said. “At first the photons don’t interact at all, but when the total energy in the system reaches a tipping point, all of a sudden, they’re all talking to each other.”

To have so many photons “talking” to one another in a lab experiment is extremely strange, akin to seeing a cat walking on hind legs.

“Normally, most particle interactions are one-on-one—two particles bouncing or attracting each other,” Schuster said. “If you add a third, they’re usually still interacting sequentially with one or the other. But this system has them all interacting at the same time.”

Their experiments only tested up to five “notes” at a time, but the scientists could eventually imagine running hundreds or thousands of notes through a single qubit to control them. With an operation as complex as a quantum computer, engineers want to simplify everywhere they can, Schuster said: “If you wanted to build a quantum computer with 1,000 bits and you could control all of them through a single bit, that would be incredibly valuable.”

The researchers are also excited about the behavior itself. No one has observed anything like these interactions in nature, so the researchers also hope the discovery can be useful for simulating complex physical phenomena that can’t even be seen here on Earth, including perhaps even some of the physics of black holes.

Beyond that, the experiments are just fun.

“Normally quantum interactions take place over length and time scales too small or fast to see . In our system, we can measure single photons in any of our notes, and watch the effect of the interaction as it happens. It’s really quite neat to ‘see’ a quantum interaction with your eye,” said UChicago postdoctoral researcher Srivatsan Chakram, the co-first author on the paper, now an assistant professor at Rutgers University.

Graduate student Kevin He was the other first author on the paper. Other co-authors were graduate students Akash Dixit and Andrew Oriani; former UChicago students Ravi K. Naik (now at UC Berkeley) and Nelson Leung (now with Radix Trading); postdoctoral researcher Wen-Long Ma (now with the Institute of Semiconductors at the Chinese Academy of Sciences); Prof. Liang Jiang of the Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering; and visiting researcher Hyeokshin Kwon of the Samsung Advanced Institute of Technology in South Korea.

Schuster is a member of the James Franck Institute and the Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering. The researchers used the Pritzker Nanofabrication Facility at the University of Chicago to produce the devices.

Citation: “Multimode photon blockade.” Chakram and He et al, Nature Physics, June 23, 2022.

Funding: Army Research Office, Packard Foundation, Samsung Advanced Institute of Technology Global Research Partnership, University of Chicago Materials Research Science and Engineering Center via National Science Foundation.”