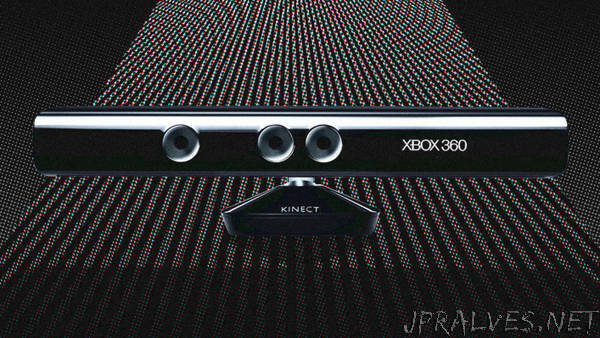

“Manufacturing of the Kinect has shut down. Originally created for the Xbox 360, Microsoft’s watershed depth camera and voice recognition microphone sold ~35 million units since its debut in 2010, but Microsoft will no longer produce it when retailers sell off their existing stock. The company will continue to support Kinect for customers on Xbox, but ongoing developer tools remain unclear. Microsoft shared the news with Co.Design in exclusive interviews with Alex Kipman, creator of the Kinect, and Matthew Lapsen, GM of Xbox Devices Marketing.

The Kinect had already been slowly de-emphasized by Microsoft, as the Xbox team anchored back around traditional gaming to counter the PS4, rather than take its more experimental approach to entertainment. Yet while the Kinect as a standalone product is off the market, its core sensor lives on. Kinect v4–and soon to be, v5–powers Microsoft’s augmented reality Hololens, which Kipman also created. Meanwhile, Kinect’s team of specialists have gone on to build essential Microsoft technologies, including the Cortana voice assistant, the Windows Hello biometric facial ID system, and a context-aware user interface for the future that Microsoft dubs Gaze, Gesture, and Voice (GGV).

Launched in 2010 with a $500 million marketing campaign, the Kinect painted a room in a discoball of invisible, infrared dots, mapping it in 3D space and allowing unprecedented tracking of the human body. The Kinect seemed perfect for getting gamers off the couch. Why press a button to duck, when you can just duck? It also enabled handy voice commands, when they worked, like “Xbox On” to turn on the Xbox One console.

As one of the first journalists to try Kinect back in 2010, though, it was immediately apparent to me that Kinect was a lot more important than what was then popularly framed as Microsoft’s Nintendo Wii killer. (Remember the Nintendo Wii?!?) It was Microsoft’s greater attempt to blur the line between the human body and the human interface–beyond the existing limitations of keyboards, mice, and even touch screens.

As I wrote at the time, “There’s something very special about using Microsoft’s Kinect system, something that separates it from every other combination of software and hardware I’ve ever used. Kinect adapts and accommodates the user. I’m not learning it; it’s learning me … I’ve never felt that a computer understood me—a flesh-and-bone human—so well.”

In the years since, I don’t believe it an exaggeration to say that Kinect has been the single most influential, or at least prescient, piece of hardware outside of the iPhone. Technologically, it was the first consumer-grade device to ship with machine learning at its core, according to Microsoft. Functionally, it’s been mimicked, too. Since 2010, Apple introduced the Siri voice assistant copying the speak-to-control functions of Kinect, and Google started its own 3D tracking system, called Project Tango (which was founded and continues to be led by Johnny Lee, who helped on the original Kinect). Vision and voice systems have become nearly ubiquitous in smartphones, and they’re gradually taking over homes, too. Take Amazon Echo bringing voice assistants to our grandparents’ living rooms–or the newer, Echo Show upping the ante by adding a camera to Alexa. Even the networked Nest Cam owes a debt to the Kinect being first through the gate, and taking the brunt of criticism on a whole new era of privacy concerns.

“Trust is something you earn in drops and lose in buckets,” says Kipman, alluding to industry-wide concern over consumer privacy. “I’d say Kinect started the process in 2010 in having to earn drops of trust. Any number of [bad] events in the world, each one, you lose a bucket.” But it wouldn’t be trust, or privacy, that would lose the Xbox consumer. It would be a fickle fanbase that thought innovation came at the price of fun.

INVENTOR VS CONSUMER

“Oh my god. Jesus. There’s my reaction. You can quote me saying, ‘Oh, comma, shit, period.’”

That’s Golan Levin, director of the esteemed Studio for Creative Inquiry at CMU, when I broke the news that Kinect is being discontinued. His lab, and others like his, use Kinect for everything from experimental art, to creating next generation UI prototypes. It’s been a vital tool to the greater research community.

“You know, we’re all at the whim of capital. And there’s no expectation that Microsoft should do something that doesn’t support their bottom line,” he continues, choosing the words of his swallowed rant very carefully. “But this is one of those times I’m sad to hear that a tool which is used for so many different applications, and is so ubiquitous, and has served crucially as a platform for so much creative experimentation, cultural progress, and secondary innovation, in so many different fields, isn’t supporting their core business.”

“Someone has made the decision that there aren’t enough games being sold that use it and it’s a shame,” he concludes. To at least some extent, that’s true.

If there’s one thing that went wrong with Kinect as a market success, you might call it “gamers.” While the device certainly had its functional flaws, including lag and occasional trouble hearing the user–it caught quick traction as an Xbox 360 accessory. The amazing games, however, never really arrived on the 360. There was no franchise with a $100 million budget developed for the Kinect, like a Call of Duty, or a Grand Theft Auto. In turn, Microsoft seems to have formulated a sensible plan. To ensure it was worthwhile for developers to invest heavily into Kinect games, it doubled down on Kinect, bundling it in every Xbox One it sold. That would ensure a larger market. However, Microsoft would also design the Xbox One to reserve a small part of its RAM and processing power, at all times, for the Kinect itself–meaning game developers couldn’t tap those resources for their own graphics and physics.

As the Xbox One was announced, it promised a living room computer that could control your games, cable box, and even, one day, your entire home, in a combination of spoken words and gestures that would be accessible to anyone. Amid innovative UI, Sony strategized the perfect counterpunch. On stage, at the E3 gaming convention just three weeks after the Xbox One’s announcement, then-CEO Jack Tretton delivered a borderline quiet speech, stating in a slow cadence that Sony “focused what gamers want most … for instance, PS4 won’t impose any new restrictions on the use of–” The discernibility of the quote cuts out there because the crowd is cheering so loud, knowing that the full system resources of the PS4 would be made available to developers. Tretton then hit on other concerns about the Xbox One, promising that Sony was a gamer’s first company, and announced a lower price for the PS4. Those sentiments echoed through message boards like Reddit, becoming something of a rallying cry to self-ascribed “hardcore gamers.” Years later, the PS4 is reported to have outsold the Xbox One by a factor of 2:1. And Microsoft, in an attempt to limbo the Xbox One’s price down and get more gaming performance out of its chipset, unbundled the Kinect and freed its dedicated system resources. The Kinect was no longer a mandatory purchase with the Xbox, diminishing any guaranteed market for Kinect game developers.

“When we introduced Xbox One, we designed it to have the best experience with the Kinect. That was our goal with the Xbox One launch,” says Lapsen. “And like all product launches, you monitor that over time, you learn and adjust.” In practice, the Xbox’s target demo cared more about a few extra polygons than some new paradigm in human-computer interaction. So Microsoft decided to invest its talents in other products.

But Levin, and other researchers like him, adored the Kinect for its forward-looking technologies. “The important thing about Kinect is it showed you could have an inexpensive depth camera. And it supported the development of thousands of applications that used depth sensing,” Levin says. He points out that it was literally Microsoft Kinect hardware that made it possible for a startup like Faceshift to exist. Built to perform extremely 3D tracking of the human face that’s suitable for biometric security, Apple acquired Faceshift to replace its thumbprint scans. And to take advantage of the technology, Apple essentially built a Kinect clone right into the iPhone X, having acquired PrimeSense in 2013, the Israeli company that developed 3D tracking technology that Microsoft licensed for the first Kinect.

“That’s one of thousands of applications Kinect made possible,” Levin continues. “Not to mention its immense impact on computer research, robotics research and interactive media arts, which is my field.” Some of Levin’s own students used Kinect to make a documentary in pointillist 3D–and then, expanded the technique to create an interactive film inside a real NYC subway car. Today, Levin points out that there are other depth-sensing cameras on the market, aside from the hackable, standalone Kinect. But he also adds that, to all the museums which feature Kinect-powered interactive art in their exhibitions? They might want to go on eBay and buy a few backups. (I suspect that Levin himself is making a trip to eBay today, too.)”