“Is there life on Venus? A new discovery suggests we should look harder.

Discovering life beyond Earth may well start with a sniff, a whiff of some chemical that scientists struggle to explain without invoking a strange, shadowy microbe. That first step has happened on Mars and on a few distant moons, and now, scientists suggest, on Venus.

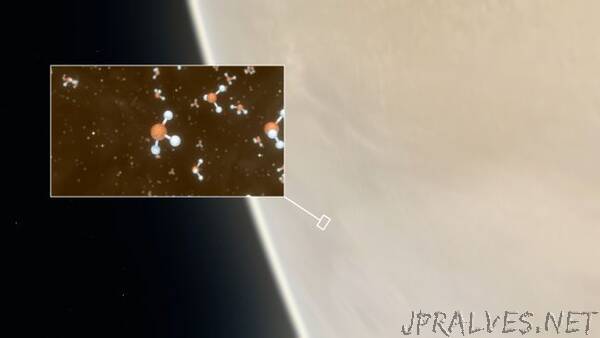

A team of astronomers announced today (Sept. 14) that it has spotted the chemical fingerprint of phosphine, which scientists have suggested may be tied to life, in the clouds of the second rock from the sun. The finding is no guarantee that life exists on Venus, but researchers say it’s a tantalizing find that emphasizes the need for more missions to the hot, gassy planet next door.

“The interpretation that it’s potentially due to life, I think, is probably not the first thing I would go for,” Victoria Meadows, an astrobiologist at the University of Washington who was not involved in the new research, told Space.com.

But it is an intriguing detection, she said, and one that emphasizes how we overlook our neighbor. “We have some explaining to do,” she continued. “This discovery especially is just another reminder of how much more we have yet to learn about Venus.”

The new research builds on the idea that, although the surface of Venus endures broiling temperatures and crushing pressures, conditions are much less harsh high up in the clouds. And scientists have realized that Earth’s own atmosphere is full of tiny life. Suddenly, microbes in the sweet spot of Venus’s atmosphere, where temperatures and pressures mimic those on Earth, don’t seem quite so outlandish.

The discovery

The scientists behind the new research wanted to look for phosphine. Researchers have recently wondered whether the chemical could be a good biosignature, a compound astronomers target in looking for life. It should break down quickly in atmospheres that are rich in oxygen, like those of Earth and Venus, and on Earth, when it isn’t being made by human industrial processes, it seems to be found near certain kinds of microbes.

Jane Greaves, an astronomer at the University of Cardiff in the U.K. and lead author of the new research, realized that she could use a telescope she knew well to check for it in the atmosphere of Venus, she told Space.com.

“Looking for it in Venus might be really peculiar, but it’s not hard to do and it wouldn’t take that many hours of telescope time,” Greaves said she thought at the time. “Why not give it a go?” So on five separate mornings in June 2017, the astronomers used the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope in Hawaii to stare at Venus.

And then the observations sat around on a computer for a year and a half, Greaves said, without her managing to find time to study them.

“I thought, well, just before we throw this away, I’ll have a final go at [analyzing the data],” she said. “There was this line and it just wouldn’t go away, and it seemed like it wasn’t imaginary anymore. I was just completely stunned.”

That line is one stripe of a spectrum, a chemical barcode that scientists can read in a telescope’s observations of light. Each chemical has its own unique fingerprint of lines and blank spaces; match enough lines and you can identify a mystery substance.

But the observations in the new research focus on only one of the lines in phosphine’s barcode, Meadows said, so she isn’t quite convinced the new findings represent a conclusive identification of phosphine.

“Until we can go and get another piece of that barcode … we can’t discriminate between which kind of barcode we’re looking at,” Meadows said. “I think they make a good case for it being phosphine in there, but I think they don’t have what I would consider a slam-dunk detection yet.”

The researchers haven’t tackled that aspect yet, but Greaves and her colleagues did arrange to use the Atacama Large Millimetre/submillimetre Array (ALMA) in March 2019 to look for the chemical again and make sure the detection wasn’t just a telescopic hiccup.

ALMA gathered a few hours of data, which also revealed more phosphine than the scientists expected — not a huge amount in the grand scheme of things, but about 20 particles out of every billion, according to the research.

“I was braced for disappointment, but it was amazing,” Greaves said.

That abundance is significantly more phosphine than she had expected to see. The way the telescopes’ observations work, the chemical must have been more than 30 miles (50 kilometers) above the Venusian surface. That’s about the same altitude at which a different recent paper with some shared co-authors suggests microbial life could survive in spore form.

So Greaves and her colleagues set to work considering what might have created all that phosphine: Perhaps volcanoes erupting or lightning striking, or perhaps meteors melting in the atmosphere or winds pulling particles off the planet’s surface. But none of these explanations seemed sufficient to them.

As usual, struggling to make more conventional explanations check out does not mean that scientists think they’ve found life. But the possibility of tiny Venusian bugs has gradually become more plausible — and researchers focused on our neighboring world say that’s important, whether or not there’s actual life to find.

“Either it’s a mistaken identity but we don’t know what the chemical is, or some strange chemistry that we are not aware of — or biology,” Sanjay Limaye, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, who wasn’t involved in the new research, told Space.com. “It’s a question of if it looks like a duck, quacks like a duck, walks like a duck, do you call it life or not? We won’t know until we go there and find out.”

Meet the mysterious phosphine

As tantalizing as the detection of phosphine on Venus may be, scientists not involved with the new research worry that it makes a few big leaps, even before the massive potential implications of a detection of life.

Some were unconvinced that phosphine was a reliable fingerprint of living organisms. The single phosphorus molecule surrounded by three hydrogen molecules is, on Earth, a rarity and short-lived: some industrial processes produce it, and it’s affiliated with some types of bacteria living in particularly strange environments. It quickly transforms in Earth’s oxygen-rich atmosphere and should in that of Venus as well, which is intriguing for scientists looking for alien breath. But the excitement about phosphine may well be premature.

“The phosphine link to the biological world is very, very faint and needs to be corroborated simply by going to the lab and doing experiments,” Tetyana Milojevic, a biochemist at the University of Vienna not involved in the new research, told Space.com.

She argues that phosphine has only been found near microbes, not produced by it, and that the compound seems to be released by the chemical decay of biological material. So before scientists can use phosphine as a potential biosignature, they need to get into the lab and really understand whether and how microbes produce phosphine, a process that scientists eyeing Mars completed for methane long ago.

Alas, those experiments aren’t quite as simple for phosphine, Matthew Pasek, an astrobiologist and geochemist at the University of South Florida who has worked on phosphorus cycling issues but was not involved in the new research, told Space.com. “Phosphine is kind of nasty, so we don’t like playing with it, so we don’t actually understand how it gets made through natural processes very well,” Pasek said. “It’s always been kind of relegated to the background of phosphorus chemistry.”

Greaves said that she’s confident phosphine is a biosignature on Earth, but does hope that the scientific community can take on these sorts of lab experiments and otherwise build on her team’s work.

The idea of phosphine as a biosignature may have another fatal flaw. Venus is now the fourth planet where scientists have detected phosphine: two gas giants and Earth. The new detection shows phosphine levels on Venus about equal to those on Jupiter and Saturn. But that’s significantly more abundant — 1,000 times more abundant — than on Earth, Pasek said.

“For the one place that it is likely biological, there’s a lot less of it even there,” he said. “So it’s kind of weird that if it is biology on Venus, that’s a whole lot of phosphine that is generating for weird reasons.”

It is Venus, after all — our mysterious neighbor.

Distance makes the science harder

Greaves and her colleagues plan to continue studying Venus from the ground, although she said that the coronavirus pandemic has interfered with those observations. Meadows said she hopes for analysis that would cover some of those other lines in the phosphine barcode. And of course some of the phosphine investigations can be done right here in laboratories.

But the details of this massive puzzle aren’t likely the sort of thing that can be seen clearly from the surface of Earth. And spacecraft tend to zip around Venus, keeping a safe distance from its hostile environments. Designing machinery that can withstand its clouds and surface is so difficult that no spacecraft has ventured into the atmosphere in decades.

“It should implore NASA and other space agencies to look at Venus as a target for astrobiology investigation, which means they should pump some money into the development of capable aerial platforms,” Limaye said of the new research.

There’s no shortage of ideas to choose from when it comes to dreamed-of Venus missions that could tackle the atmosphere, whether your taste runs to more traditional designs or unorthodox options like blimps, balloons or commercially built spacecraft.

“It’s time to figure out Venus,” James Garvin, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, who wasn’t involved in the new research but is the principal investigator on a Venus atmospheric probe mission that NASA is evaluating, told Space.com. “If we ignore it too long, we could be missing the forest for the trees, and that would never be good.”

He thinks engineering has caught up with the challenges of the Venusian atmosphere.

“The time is ripe for thinking about what the atmosphere is telling us within itself. It’s just this beautiful laboratory next door that has been tough enough that we’ve ignored it for 35 years,” Garvin said. “The atmosphere is kind of calling us, whispering in the night, ‘Hey, I may have something that you should think about.’ And we haven’t been.”

The research is described in a paper published today (Sept. 14) in the journal Nature Astronomy.”