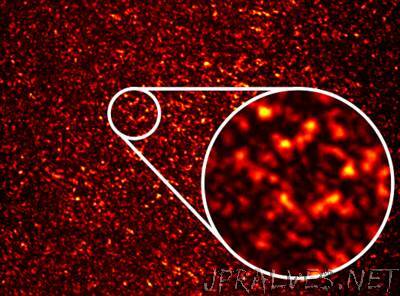

“A breakthrough innovation in the measurement of lasers can measure changes one millionth of the size of an atom and could revolutionise their use in quantum technologies and healthcare thanks to new, lower-cost technology. A team from the University of St Andrews and UK company M Squared Lasers has used the principle of random scattering of light to create a new class of laser wavemeter that breaks through a glass ceiling in the way wavelength is measured. Wavemeters are used in many areas of science to identify the wavelength (i.e. colour) of light. All atoms and molecules absorb light at very precise wavelengths, therefore the ability to identify and manipulate them at high resolution is important in diverse fields ranging from the identification of biological and chemical samples to the cooling of individual atoms to temperatures colder than the depths of outer space. Waves, whether they are water waves or light waves, interact via interference: sometimes two waves reach a peak at the same time and place and the result is a higher wave, but it is also possible that a peak of one wave meets the trough of another, resulting in a smaller wave. The combination of these effects produces an interference pattern. Conventional wavemeters analyse changes in the interference pattern produced by delicate assemblies of high-precision optical components. The cheapest instruments cost hundreds or thousands of pounds, and most in everyday research use cost tens of thousands. In contrast, the team realised a robust and low-cost device which surpasses the resolution of all commercially available wavemeters. They did this by shining laser light inside a 5cm diameter sphere which had been painted white, and recording images of the light which escapes through a small hole. The pattern formed by the light is incredibly sensitive to the wavelength of the laser. Dr Graham Bruce from the School of Physical and Astronomy explains: “If you take a laser pointer, and shine it through Sellotape or on a rough surface like a painted wall, on closer inspection of the illuminated surface you’ll see that the spot itself looks grainy or speckled, with bright and dark patches. This so-called ‘speckle pattern’ is a result of interference between the various parts of the beam which are reflected differently by the rough surface.”

Link to article